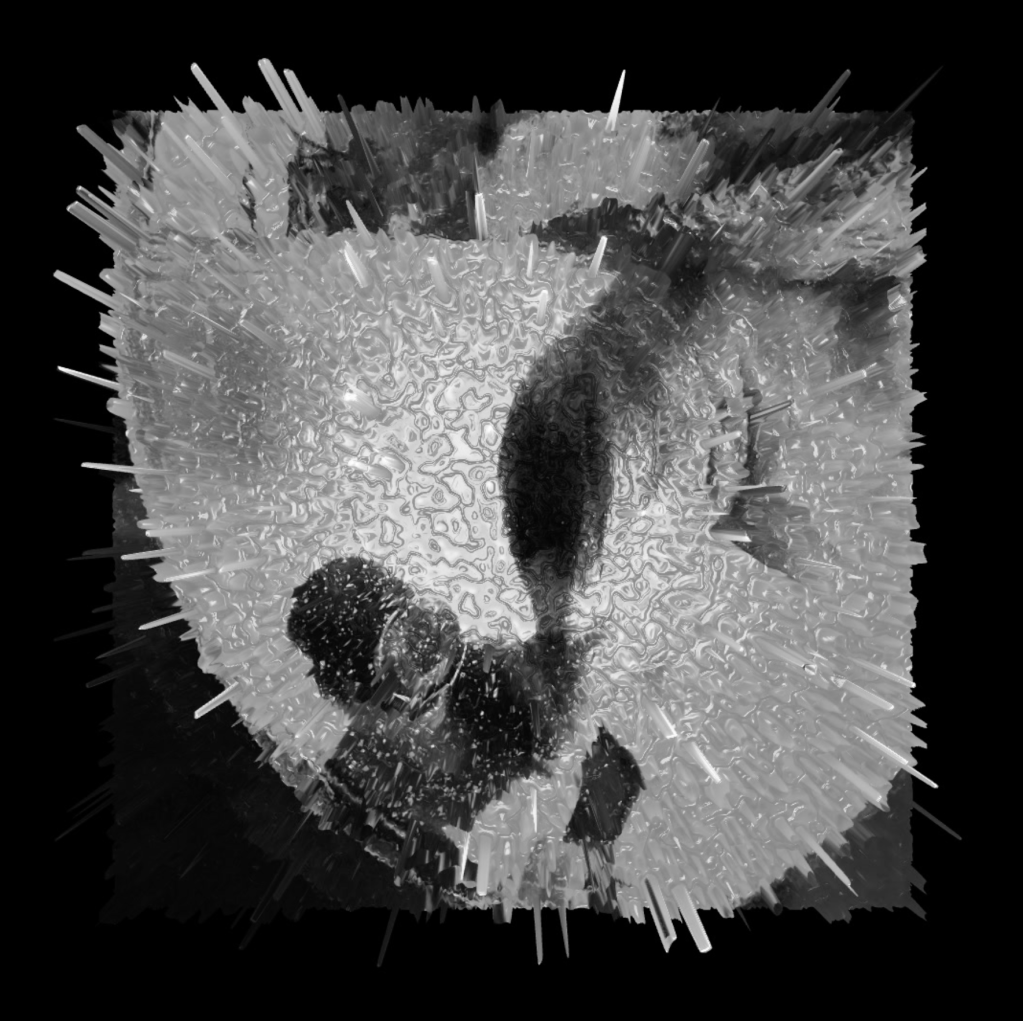

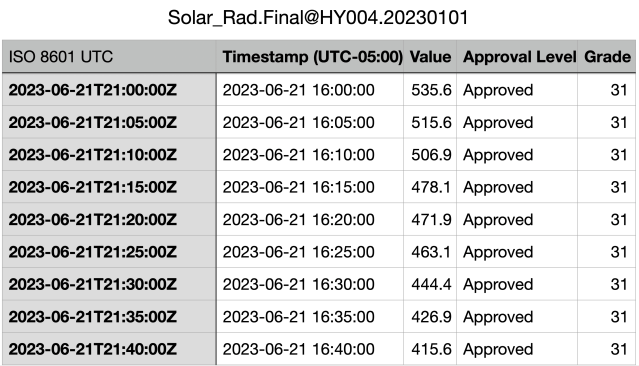

Photograph of Margaret Howe and a dolphin on the flooded balcony at the Communication Research Institute, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. Image: John C. Lilly Papers, M0786. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California.

Refractions is a sound and projection installation that reimagines Cold War-era dolphin-human communication research through archival audio, data sonification, and storytelling, revealing the entanglement of this work with military-scientific infrastructures and using the concept of “refraction” to explore how sound, signals, and histories shift as they move across mediums, institutions, and species.

tary and scientific remote sensing infrastructures. The composition is based on archival recordings produced at John C. Lilly’s Communication Research Institute’s (“CRI”) Dolphin Point Laboratory in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands where Lilly and his team carried out an ambitious research program that aimed to establish two-way communication between humans and dolphins.

The installation’s guiding creative principle is notion of “refraction,” or the process of distorting, bending and altering the direction of a signal as it moves from one medium into another. For military scientists, and for the team at the CRI, refraction was a challenge to be overcome since it distorts sounds as they move from air into water, and vice versa. Devices such as hydrophones (underwater microphones) were designed to overcome this problem. In my project, I use refraction as a way of thinking about the possibilities for intervening in the way archival documents and sound recordings travel through institutional spaces and their effects on bodies and material environments.

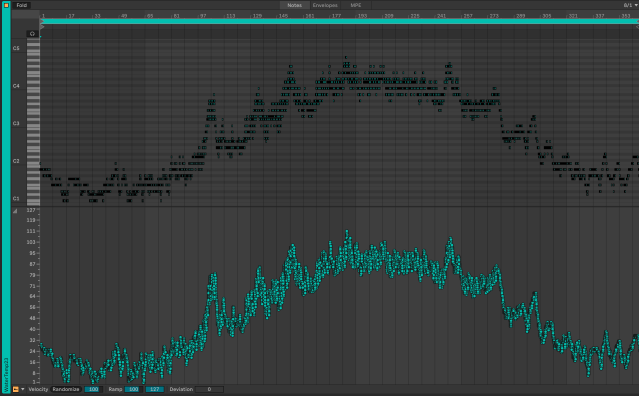

Refractions began as a tool for research on the history of the CRI. I initially arranged the archival recordings into “rooms” on a Digital Audio Workstation so that I could listen to them in a systematic but non-linear way as part of my research on this history of sound in the Cold War. Gradually, the DAW setup and the processed recordings evolved into Refractions, which recreates the soundscape of St. Thomas facility and, just as importantly, retraces the institutional and technological networks that supported and shaped the CRI.

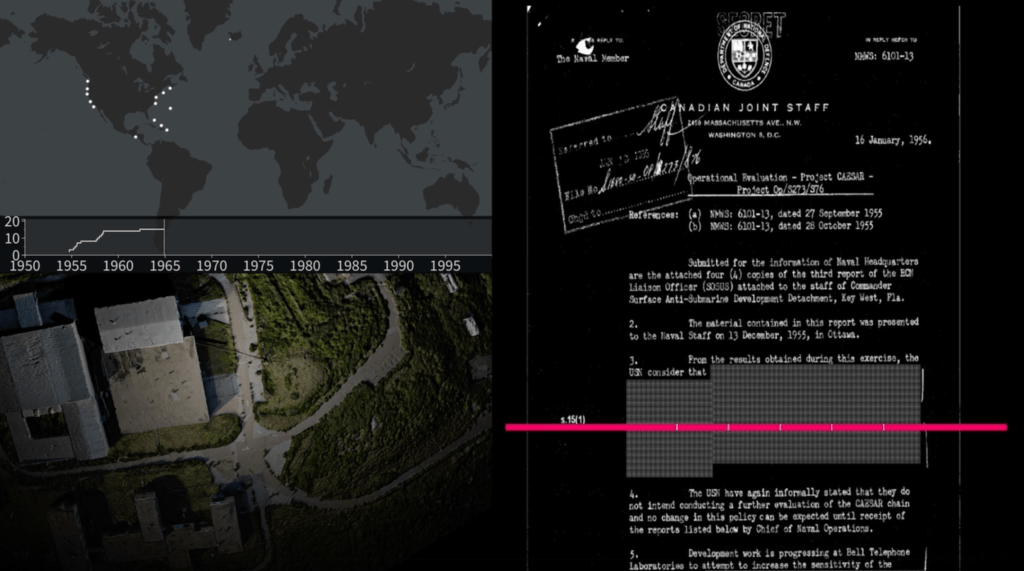

The U.S. Navy, Air Force, NASA, among other scientific and military institutions, provided funding and other support to the CRI to develop the St. Thomas facility and carry out a novel but controversial research program on human-dolphin communication. These institutions had a shared interest in advancing Lilly work for various Cold War-related ends related to the conquest of vertical space (ocean, atmosphere, outer space).

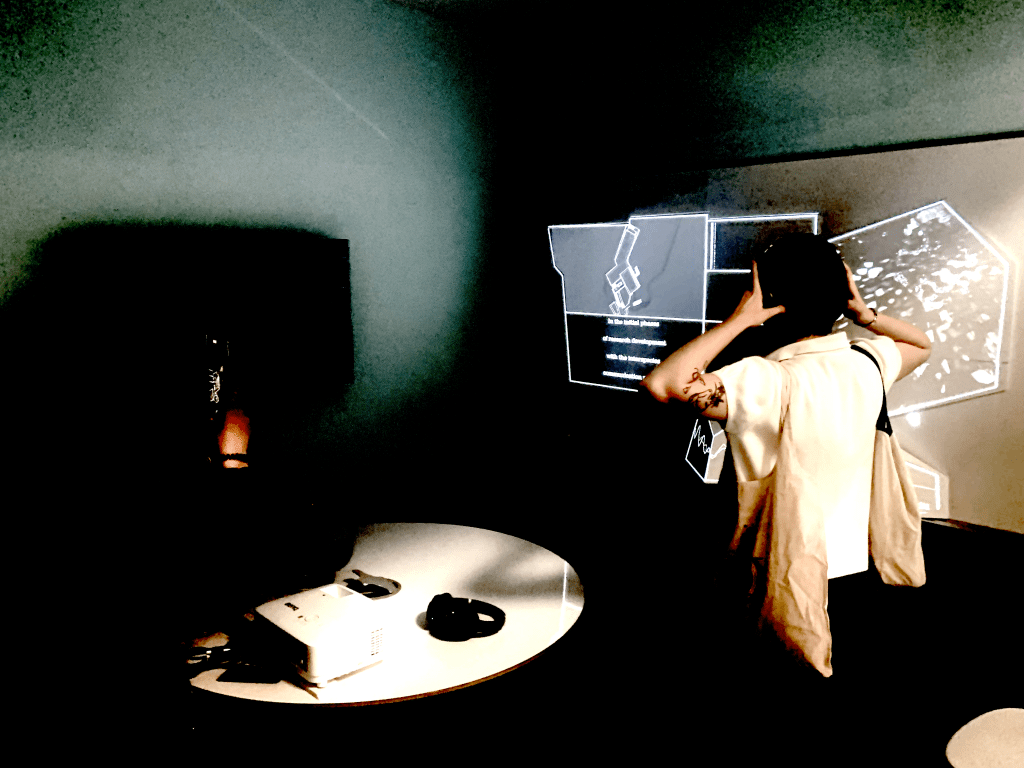

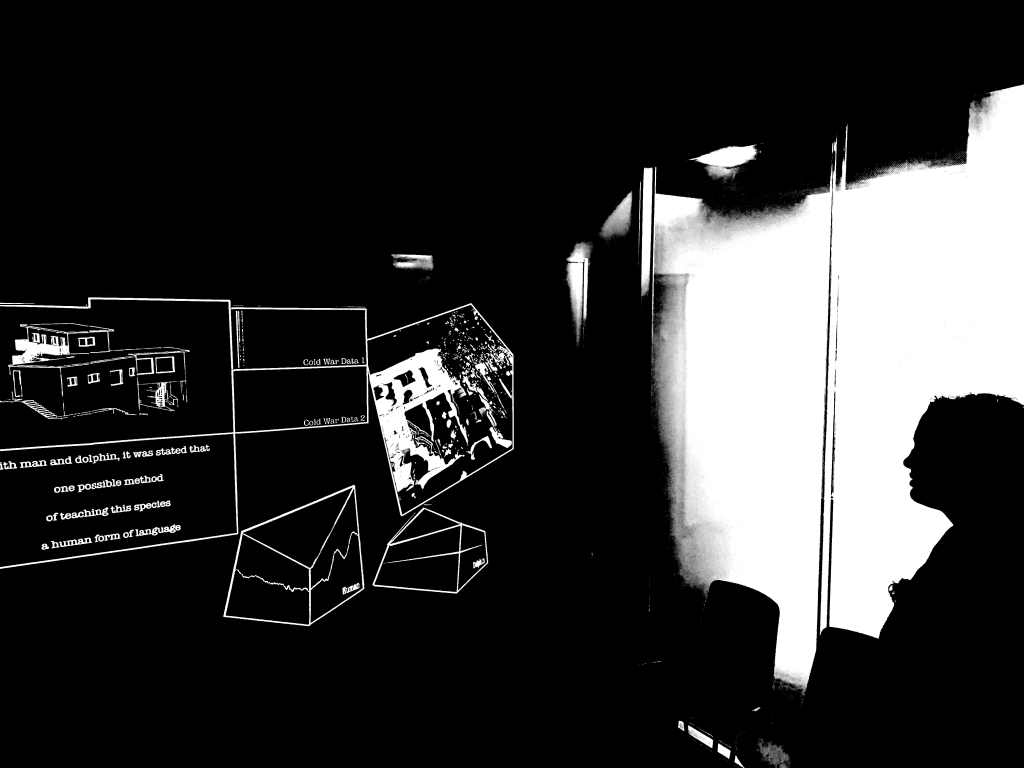

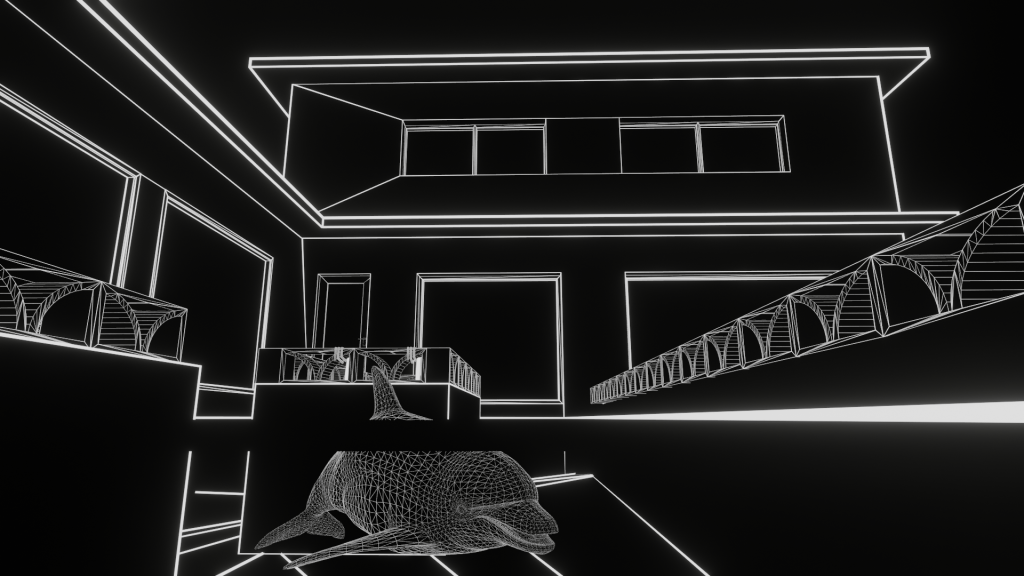

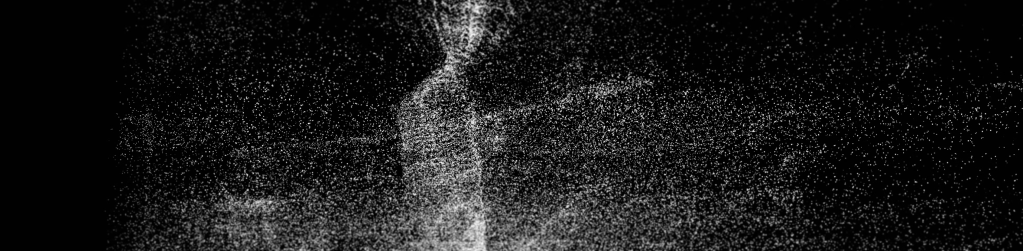

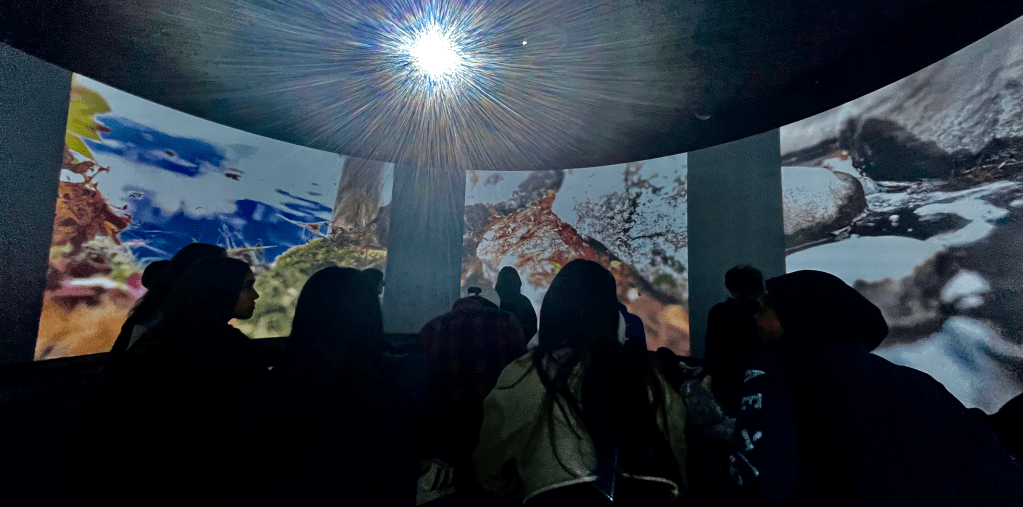

Images of The Dolphin House installation, including stills from the video component and photographs of audience interaction. Images: John Shiga.

One of Lilly’s key collaborators, who can be heard in several parts of installation, was Margaret Howe. Howe was a key figure in the development and implementation of a months-long experiment in which she would live with a dolphin 24-hours a day for several months to accelerate the “reprogramming” of dolphins to communicate with humans (a story that has been retold in a number of news stories in recent years as well as a BBC documentary). The redesigned lab, informally referred to as the “flooded house” or the “dolphin house,” was configured to facilitate prolonged human and dolphin cohabitation through, for example, rooms and a balcony flooded with 18 inches of water. It was also fitted with microphones suspended from the ceilings to record dolphin vocalizations as well as Plexiglas tanks in which dolphins would listen to recordings of human speech and be rewarded with fish for attempting to mimic the sounds of the humans. Just as the house was flooded to bring human and dolphin participants close together for weeks or even months at a time, so too the house was saturated with acoustic technologies for capturing and manipulating the vocal sounds of humans and dolphins.

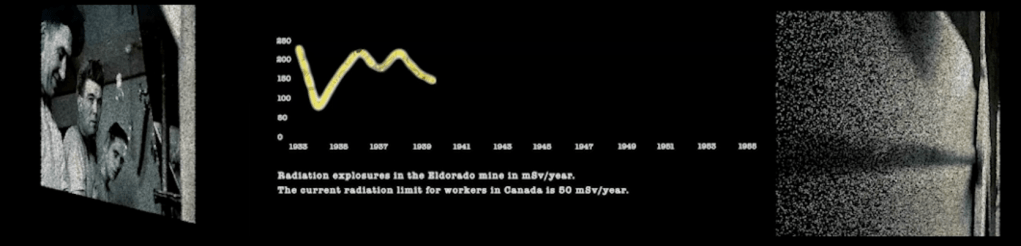

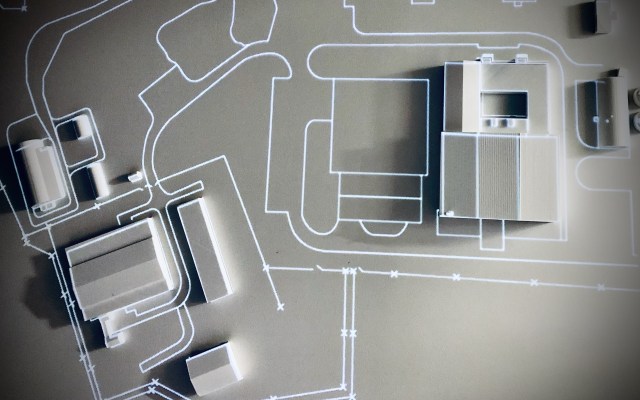

Unintentionally, the recording system picked up various types of “noise”: elemental (e.g., water and wind), technological (e.g., tape hiss), and social (conversations that were not so much documenting interspecies communication research but expressing frustration with various aspects of working at the lab). These noises have been processed and arranged in installation to create a “sonic blueprint” of the CRI and its interior spaces. Like the blueprint for a building, which outlines the spaces for people and objects as well as the underlying infrastructure, the sound composition of the installation has several layers which in this case correspond to human-dolphin communication research practices and the military-scientific apparatus that supported it. The sound composition pieces together parts of the CRI’s archival recordings into separate streams of sound for humans and dolphins which periodically interact. Additionally, the sound composition situates the CRI’s work within the broader military-scientific infrastructure of remote sensing. The installations other sonic layers were produced by “following the money,” that is, by retracing the CRI’s funding agencies and their activities around the world during the 1960s. In this way, the installation foregrounds what was so often left out of contemporaneous popular media and scientific discourse about Lilly’s work: the fact that the CRI was, from a military perspective, one node among many in a planet-spanning network of command, control and communication.

The composition is organized into seven parts, each of which focuses on a specific room or facility in the CRI and the sonic environment created by the interaction of the building with the technological and natural environments in which it was embedded as well as the human and nonhuman actors who inhabited the various spaces of the lab. Here is an excerpt from “Dolphin Elevator” – a segment of the composition set in the facility’s sea pool:

Featuring the voice of one of the CRI researchers (possibly its former director, Gregory Bateson, though this isn’t indicated in the archives’ note for this audio tape), the sound composition turns to a seemingly tranquil moment in the archival recordings. In keeping with the practice of the CRI, the researcher describes what he is seeing and hearing as a way of providing an auditory version of a lab report or field notes. In this instance, one of dolphins is being moved onto the elevator from the sea pool (used mainly for visual observation through a large window at the base of it) to the upstairs pool (used mainly for audio recording since it was shielded to some degree from the wind and sounds of the ocean). Texturally, the composition gestures to the openness and optimism of the researchers in the early years of the project. At the same time, the high frequency “beeps” are sonifications of the U.S. military’s Corona spy satellite program. Each of the ten beeps (the sequence repeats in a loop) represents approximately 100 images (the Corona satellite captured 930 images in 24 hours on November 19, 1964). The pitch represents the latitude of the area captured in each photograph and the beep’s position in the stereo field represents its longitude. The locations are in the following order (using 1965 names): Soviet Union (northeast), Tibet, China, Kazakh SSR, Soviet Union (Moscow), Republic of Congo, Cuba, Haiti, Atlantic Ocean approximately 300 miles from San Francisco, Soviet Union (northeast).

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Philip Bailey and the Estate of John C. Lilly for giving me permission to use the Communication Research Institute’s audio recordings in this installation. I would also like to thank the staff of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Stanford University for their invaluable advice and support.