-

Audible Oceans: Media Archeology of the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS)

During the Cold War, a network of underwater microphones (“hydrophones”) and listening stations in US, Canada, the Bahamas, Iceland and Wales monitored sound in the Atlantic in order to detect and track Soviet submarines. Today, some of the abandoned listening stations are still standing, though they are rapidly deteriorating. Using photography, field recording, animation and…

-

Becoming Radiogenic: Nuclear Violence, Contamination and Epistemic Agency

This research-creation project consists of a series of audiovisual compositions, which work together to trace the discursive and material strategies of nuclear imperial power in Canada, the United States and Japan. The guiding question of this work concerns the agency of “radiogenic communities,” which have often been regarded as social effects of nuclear colonialism and…

-

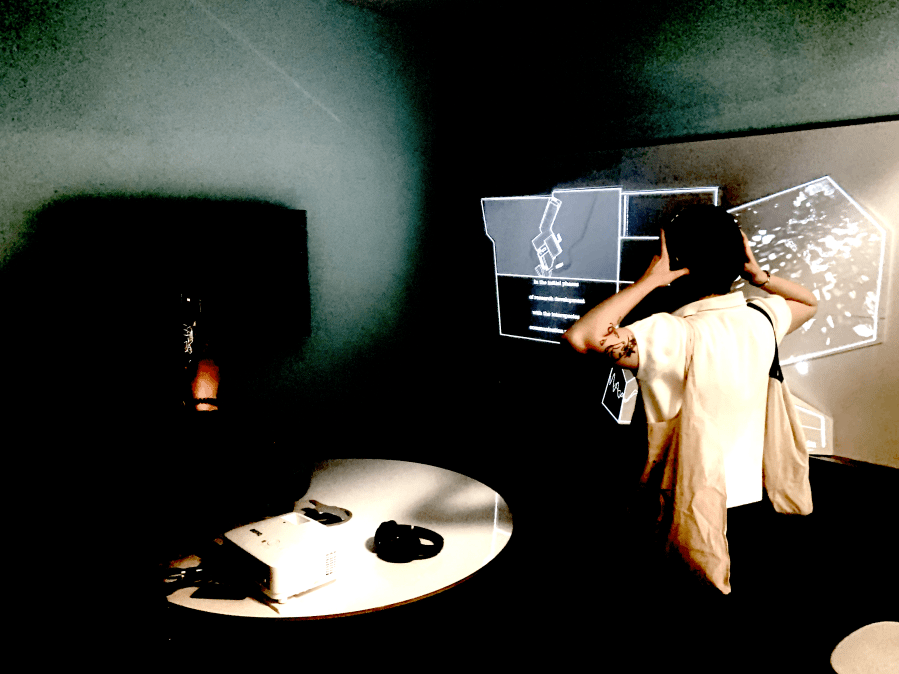

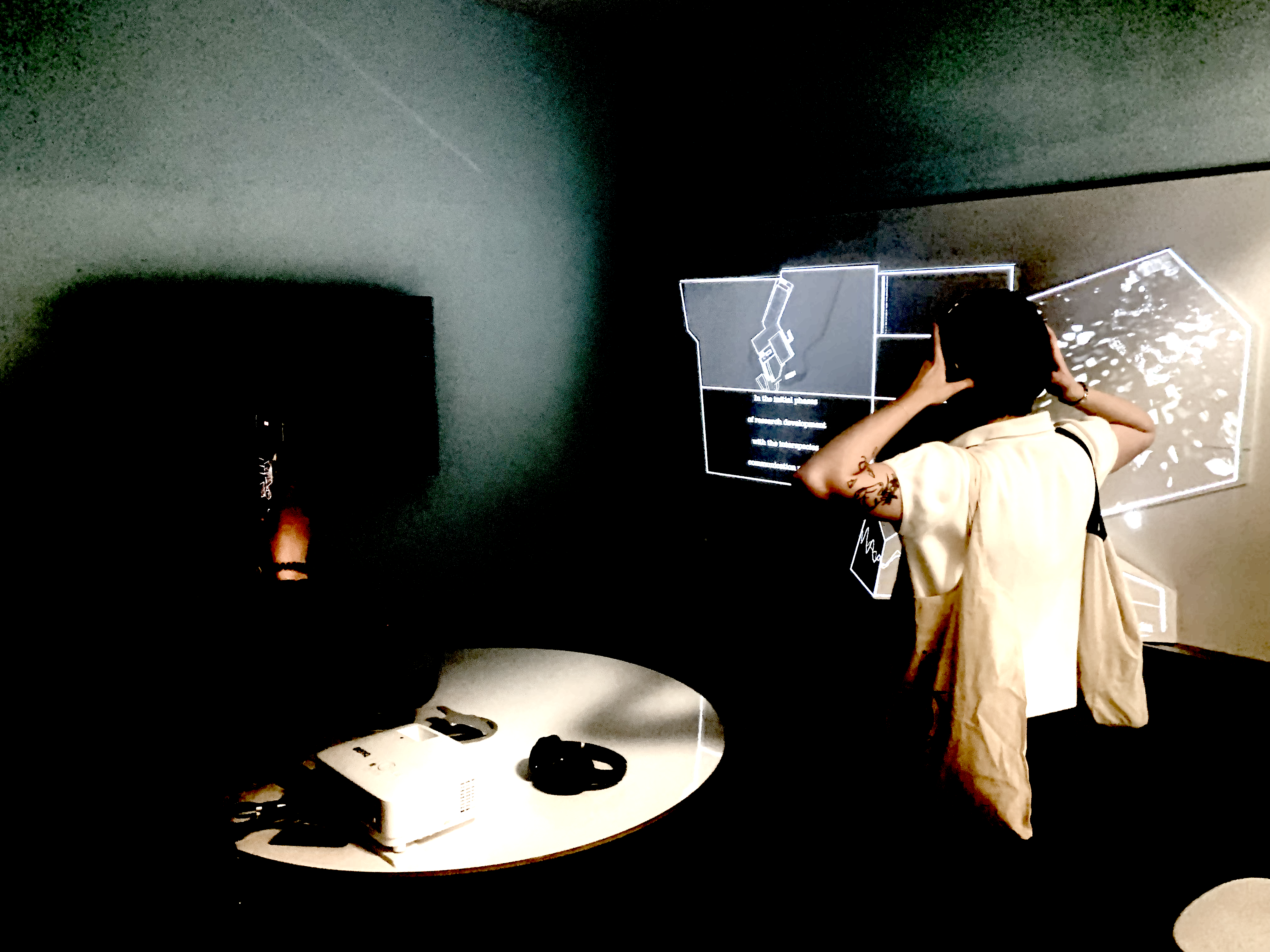

Refractions: Making Cold War Archives Audible

Photograph of Margaret Howe and a dolphin on the flooded balcony at the Communication Research Institute, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. Image: John C. Lilly Papers, M0786. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California. Refractions is a sound and projection installation that reimagines Cold War-era dolphin-human communication research through archival audio,…

-

The River as Data: Sonifying Smart Governance

The River as Data transforms a year of high-resolution environmental data from Toronto’s Don River into a multi-channel audiovisual composition. Drawing from open datasets and solar activity records, I developed a custom Python tool to map water levels, solar radiation, and temperature fluctuations to sound and image. The project is rooted in a critical engagement…